Crawdad Text Analysis Software

Posted in:admin

Sitemap Search: 4455 - New Directions in Parks and Open Space System Planning, Megan Lewis 7702, Jules J. Berman 6698, Lia Leendertz 331183390 - Your Step-By-Step Guide to Success, Entrepreneur Press, Rich Mintzer 0089, J.

Robl 3392, Unknown 889X 9902, Llyn Hunter 9917, Williams,Rowan 8832 - Materials, Technology, and New Applications, Kazunori Ozawa 4409 - The Story of Jungle Larry, Safari Jane, and David Tetzlaff, Sharon Rendell-Smock 9961, Monica L. Rausch 8892 - Current Issues, Atul K.

Saxena 8805, Alfonso Blanco Nespereira 0043 - Crusade for Standards, Angela Cornforth, Tony Evans 900, Deep Purple 4414, Kalulal Shrimali, K L Shrimali, George S Counts 3396 - Lessons in Phraseology, Punctuation, and Sentence Structure (1903), Helen Josephine Robins, Agnes Frances Perkins 4481 - From Genomes to Drugs, Thomas Lengauer, Raimund Mannhold, Hugo Kubinyi. 1183, Johann Hermann Heinrich Schmidt, John Williams White 628, Birdsong 561, Laurent VERNEY 991, Daniel Belleza & OS Coracoe Em, Daniel Belleza, OS Coracoe Em 9910 - An Analysis of Cases and Concepts, Christopher Slobogin, Charles H Whitebread 111X - The Need for Change, Lynne Harne 9913, U.S.

Congress 623, Hunter Ian 2227, Manville George Fenn 2246, Leeanne E. Alonso, Jennifer McCullough, Piotr Naskrecki. 461723, Guns 'n Roses, Jim Mitchell 3325, J. Jackson 110X - Selections from 'Vince Neil Exposed' - Authentic Guitar Tab Edition, Jo Novark 2258, Georg Ebers 0098 - Drums, Alfred Publishing 696, Xandria 235, The New Archie Shepp Quartet 223321482, H.

P Blavatsky, Ramiro Garcia Vega 4431, Alan Brinkley 9981, Andrew Kelly 079727, Olafur Arnalds 2277, Ian Kershaw 9968, Tyler E. Bagwell, Jekyll Island Museum 1154, William Shakespeare 3381, Ismail Kadare 444473877, Liz Paren, Gill Stacey 889, Vigil 6649, Blue Mountain Press 1156, Nathaniel William Taylor 9982 - India's Long Road to Independence, Anthony Read, David Fisher 4423 - A Sufferer for the Truth (1912), Ernest E. Taylor 4410 - Lightening up Recipes from Famous Restaurants, Elaine Magee 2227, Ley 8808, Patrick O'Brian 0083, JS Thomas 2252, Danielle Henderson 3389, Diane Carmel Leger, Dar Churcher 8837 - An Introductory Grammar, Robert Ray Ellis 9945, Patricia Shannon 8857 - Genocide in Rwanda, Alan J.

Jan 25, 2017. • Corman, S., and Dooley, K. (2007), Wonkosphere 1.0, Chandler, Arizona: Crawdad Technologies. • Dooley, K., and Corman, S. (2007), Crawdad Listening Post 1.0, Chandler, Arizona: Crawdad. Technologies, LLC. And Dooley, K. (2006), Crawdad Text Analysis System 2.0,.

Kuperman 4413 - A Study in Provincial Toryism, V. Chittick 7786, William J. Spencer 1181, J. Romn 5508, Nathan McCall 5584 - Tidbits for the New Millennium!, Maxwell Pinto 3375, Bernard Cornwell 1153 - The Form of the Ancient Greek Letter, Francis Xavier J. Exler 3377, Flaminio Gualdoni 667X - A Rally of Men, E. V Lucas 3358, Sandi Patti 8857, Veronica Ross 0006, Lisa Schnebly Heidinger, Janeen Trevillyan, Sedona Historical Society 5524 - A Practical Approach, Olwyn Westwood, Frank Hay 3366, Robbins, Decenzo 9936, Selma Lagerlof 5561, Michael D Oates, Larbi Oukada, Rick Altman 335X - The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda 1994-1999, Andre Klip, Goran Sluiter 3367 - More Experiments in Atmospheric Physics, Craig F.

Bohren, David Jones 8842 - Teacher's Resource Book, Daniele Bourdais, Sue Finnie, Anna Lise Gordon 1175, Albert Frank 0032, Edith Wharton 1188 - A Lift-the-flap Book, Adrienne Kennaway 2254 - Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute, Held in Kiev, Ukraine, June 18-28, 2000, Marie-Isabelle Baraton, Irina Uvarova 2230 - The People's Republic, 1949-1976, Jean Chesneaux 9966, Thomas Ratliff, David Antram 1166, Susanna Moore 2204, John W. Griffith, Charles H. Frey, Melissa Payton 668805956 - Vol. 06 on the Eve of America's Entrance into World War I, 1915-1916, Philip S. Foner 4432 - Two Hundred Years of the M.C.C., Tony Lewis 2267 - Abel Heywood & Son's Guide Book, C195503652, Sol Theron De Lee 9913 - The Experiences of Young People from Different Ethnic Groups, Ravinder Barn, Linda Andrew, Nadia Mantovani 440X - I Want My Stuff, Evaughn High 1175, Sharif Gemie 2258, Vincent M.

Using Computerized Text Analysis to Assess Threatening Communications and Behavior Cindy K. Chung and James W. Pennebaker Understanding the psychology of threats requires expertise across multiple domains.

Not only must the actions, words, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors of the person making a threat be examined, but the world of the recipient of the threats also needs to be understood. The problem is more complex when considering that threats can be made by individuals or groups and can be directed toward individuals or groups. A threat, then, can occur across any domain and on multiple levels and must be understood within the social context in which it occurs. Within the field of psychology, most research on threats has focused on the nonverbal correlates of aggression. In the animal literature, for example, considerable attention has been paid to behaviors that signify dominance or submission.

Various species of birds, fish, and mammals often change their appearance by becoming larger when threatening others. Dominance and corresponding threat displays have also been found in vocalization, gaze, and even smell signals (e.g., Buss, 2005). In the literature on humans, an impressive number of studies have analyzed threatening behaviors by studying posture, facial expression, tone of voice, and an array of biological changes (Hall et al., 2005). Although nonverbal features of threats are clearly important, many of the most dangerous threats between people are conveyed using language.

Whether among individuals, groups, or entire nations, early threats often involve one or more people using words to warn others. Despite the obvious importance of natural language as the delivery system of threats, very few social scientists have been able to devise simple systems to identify or calibrate language-based threats.

Only recently, with the advent of computer technology and the availability of large language-based datasets, have scientists been able to start to identify and understand threatening communications and responses to them through the study of words (Cohn et al., 2001; Pennebaker and Chung, 2005, 2008; Smith, 2004, 2008; Smith et al., 2008). This paper provides a general overview of computerized language assessment strategies relevant to the detection and assessment of word-based threats. It is important to appreciate that this work is in its infancy. Consequently, there are no agreed-on methods or theories that have defined the field.

Indeed, the “field” is currently made up of a small group of laboratories generally working independently with very different backgrounds and research goals. The current review explores threats from a decidedly social-psychological perspective. As such, the emphasis is on the ways in which word use can reveal important features of a threatening message and also the psychological nature of the speaker and the target of the threatening communication. Whereas traditional language analyses have emphasized the content of a threatening communication (i.e., what the speaker explicitly says), this review focuses on the language style of the message, especially those words that people cannot readily manipulate (for a review, see Chung and Pennebaker, 2007). This is especially helpful in the area of assessing threatening communications and actual behavior because subtle markers of language style (e.g., use of pronouns or articles) can reveal behavioral intent that the speaker may be trying to withhold from the target. Finally, this paper discusses methods that have the goal of automated analyses and largely draws on word count approaches, which are increasingly being used in the social sciences. Computerized tools are especially helpful for establishing a high standard of reliability in any given analysis and for real-time or close to real-time assessment of threatening communications, so that our analyses might one day lead to interventions as opposed to just retrospective case studies.

This paper also briefly describes common automated methods available to study language content and language style. Next, a classification scheme for different types of threats is presented that serves as the organizing principle for this review. The next section summarizes empirical research that has been conducted to assess intent and actual behaviors in. TEXT ANALYSIS METHODS Features of language or word use can be counted and statistically analyzed in multiple ways.

The existing approaches can be categorized into three broad methodologies: (1) judge-based thematic content analysis, (2) computerized word pattern analysis, and (3) word count strategies. All are valid approaches to understanding threatening communications and can potentially yield complimentary results to both academic and nonacademic investigators. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to review each approach in detail, an overview is given below. Then the discussion focuses on word count strategies, which serve as the basis for the remainder of the review. Judge-Based Thematic Content Analysis Qualitative approaches use an expert or a group of judges to systematically rate particular texts along various themes. Such approaches have explored the subjective or psychological meaning of language within a phrase or sentence (e.g., Semin et al., 1995), conversational turn (e.g., Tannen, 1993), or an entire narrative (e.g., McAdams, 2001).

Thematic content analyses have been widely applied for studying a variety of psychological phenomena, such as motive imagery (e.g., Atkinson and McClelland, 1948; Heckhausen, 1963; Winter, 1991), explanatory styles (Peterson, 1992), cognitive complexity (Suedfeld et al., 1992), psychiatric syndromes (Gottschalk et al., 1997), and goal structures (Stein and Albro, 1997). Several problems exist with qualitative approaches to text analysis. Judge-based coding requires elaborate coding schemes, along with multiple trained raters. The reliability of judges’ ratings must be assessed and reevaluated early in the process through extensive discussions. Consideration of time and effort has limited analyses of this kind to small numbers of individuals per analysis. For the analysis of completely open-ended text, for example, when a series of very different threatening communications are assessed for the probability of leading to actual threatening behaviors, the coding schemes developed in judge-based thematic content analysis may not be applicable or particularly relevant to any new threat or document.

As a side note, the authors have spoken with and read about a number. Of “expert” language analysts who often market their own language analysis methods. Some of these approaches claim to reliably assess deception, author identification, or other intelligence-relevant dimensions. Often, it is claimed that the various methods have accuracy rates of more than 90 to 95 percent. To our knowledge, no human-based judge system has ever been independently assessed by a separate laboratory or been tested outside of experimentally produced and manipulated stimuli. Given the current state of knowledge, it is inconceivable that any language assessment method—whether by human judges or the best computers in the world—could reliably detect real-world deception or other psychological quality at rates greater than 80 percent, even in highly controlled datasets.

This issue will be discussed in greater detail later. Computerized Word Pattern Analysis Rather than exploring text “top down” within the context of previously defined psychological content dimensions, word pattern strategies mathematically detect “bottom up” how words covary across large samples of text (Foltz, 1996; Poppin, 2000) or the degree to which words overlap within texts (e.g., Graesser et al., 2004). One particularly promising strategy is Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA; see, e.g., Landauer and Dumais, 1997), which is a method used to learn how writing samples are similar to one another based on how words are used together across documents. For example, LSA has been used to detect whether or not a student essay has hit all the major points covered in a textbook or the degree to which a student essay is similar to a group of essays previously graded with top grades on the same topic (e.g., Landauer et al., 1998). Not only can word pattern analyses detect the similarity of groups of text, they can also be used to extract the underlying topics of text samples (see Steyvers and Griffiths, 2007). One example of a topic modeling approach in the social sciences is the Meaning Extraction Method (MEM; Chung and Pennebaker, 2008). MEM finds clusters of words that tend to co-occur in a corpus.

The clusters tend to form coherent themes that have been shown to produce valid dimensions for a variety of corpora. For example, Pennebaker and Chung (2008) found MEM-derived word factors of al-Qaeda statements and interviews that differentially peaked during the times when those topics were most salient to al-Qaeda’s missions. MEM-derived factors have been shown to hold content validity across multiple domains. Since the MEM does not require a predefined dictionary (only characters separated by spaces), and translation occurs only at the very end of the process, MEM has served as an unbiased way to examine psychological constructs across multiple languages (e.g., Ramirez-Esparza et al., 2008, in press; Wolf et al., 2010a, 2010b). Word pattern analyses are generally statistically based and therefore require large corpora to identify reliable word patterns (e.g., Biber et al., 1998). Some word pattern tools feature modules developed from discourse processing, linguistics, and communication theories (e.g., Crawdad Technologies; Graesser et al., 2004), representing a combination of top-down and bottom-up processing capabilities.

Overall, word pattern approaches are able to assess high-level features of language to assess commonalities within a large group of texts. Word Count Strategies The third general methodology focuses on word count strategies. These strategies are based on the assumption that the words people use convey psychological information over and above their literal meaning and independent of their semantic context. Word count approaches typically rely on a set of dictionaries with precategorized terms. The categories can be grammatical categories (e.g., adverbs, pronouns, prepositions, verbs) or psychological categories (e.g., positive emotions, cognitive words, social words).

While grammatical categories are fixed (i.e., entries belong in one or multiple known categories), psychological categories are formed by judges’ ratings on whether or not each word belongs in a category. Computerized software can then be programmed to categorize words appearing in text according to the dictionary that it references. Accordingly, these programs typically allow for the use of new, user-defined dictionaries, enabling broader or more specific sampling of word categories. Today, there is an ever-increasing number of applications of word count analyses in clinical psychology (e.g., Gottschalk, 1997), criminology and forensic psychology (e.g., Adams, 2002, 2004), cultural and cross-language studies (e.g., Tsai et al., 2004), and personality assessments (e.g., Pennebaker and King, 1999; Mehl et al., 2006). An increasingly popular tool used for text analysis in psychology is Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker et al., 2007).

LIWC is a computerized word counting tool that searches for approximately 4,000 words and word stems and categorizes them into grammatical (e.g., articles, numbers, pronouns), psychological (e.g., cognitive, emotions, social), or content (e.g., achievement, death, home) categories. Results are reported as a percentage of words in a given text file, indicating the degree to which a particular category was used.

The words in LIWC categories have previously been validated by independent judges, and. Use of the categories within texts has been shown to be a reliable marker for a number of psychologically meaningful constructs (Pennebaker et al., 2003; Tausczik and Pennebaker, 2010).

Using LIWC, word counts have been shown to have modest yet reliable links to personality and demographics. For example, one study across 14,000 texts of varying genres found that women tend to use more personal pronouns and social words than men and that men tend to use more articles, numbers, and fewer verbs (Newman et al., 2008). Together, these findings suggest that women are more socially oriented and that men tend to focus more on objects.

Word count tools have effectively uncovered psychological states from spoken language (e.g., Mehl et al., 2006), in published literature (e.g., Pennebaker and Stone, 2003), and in computer-mediated communications (e.g., Chung et al., 2008; Oberlander and Gill, 2006). There is also evidence that word counts are diagnostic of various psychiatric disorders and can reflect specific psychotic symptoms (Junghaenel et al., 2008; Oxman et al., 1982).

For example, Junghaenel and colleagues found that psychotic patients tend to use fewer cognitive mechanism and communication words than do people who are not suffering from a mental disorder, reflecting psychotic patients’ tendencies to avoid in-depth processing and their general disconnect from social bonds. These studies provide evidence that word use is reflective of thoughts and behaviors that characterize psychological states. Word counts provide meaningful measures for a variety of thoughts and behaviors.

LANGUAGE CONTENT VERSUS LANGUAGE STYLE Most early content analysis approaches by both humans and computers focused on words related to specific themes. By analyzing an open-ended interview, a human or computer can detect theme-related words such as family, health, illness, and money.

Generally, these words are nouns and regular verbs. Nouns and regular verbs are “content heavy” in that they define the primary categories and actions dictated by the speaker or writer. It makes sense; to have a conversation, it is important to know what people are talking about.

However, there is much more to communication than content. Humans are also highly attentive to the ways in which people convey a message. Just as there is linguistic content, there is also linguistic style—how people put their words together to create a message. What accounts for “style”? Consider the ways by which three different people might summarize how they feel about ice cream.

Person A: I’d have to say that I like ice cream. Person B: The experience of eating a scoop of ice cream is certainly quite satisfactory. Person C: Yummy. The three people differ in their use of pronouns, large versus small words, verbosity, and other dimensions. We can begin to detect linguistic style by paying attention to “junk words”—those words that do not convey much in the ways of content (for a review, see Chung and Pennebaker, 2007; Pennebaker et al., 2003). These junk words, usually referred to as function words, serve as the cement that holds the content words together.

In English, function words include pronouns (e.g., I, they, it), prepositions (e.g., with, to, for), articles (e.g., a, an, the), conjunctions (e.g., and, because, or), auxiliary verbs (e.g., is, have, will), and a limited number of other words. Although there are less than 200 common function words, they account for over half of the words used in everyday speech. Function words are virtually invisible in daily reading and speech. Even most language experts could not tell if the past few paragraphs have used a high or low percentage of pronouns or articles. People are reliable in their use across contexts and over time.

Although most everyone uses far more pronouns in informal settings than in formal ones, the highest pronoun use in informal contexts tends to be by the same people who use pronouns at high rates in formal contexts (Pennebaker and King, 1999). Analyzing function words at the paragraph, page, or broader text level completely ignores context. The ultimate difference between the current approach and more traditional linguistic strategies is that function words tell us about the psychology of the writer/speaker rather than what is explicitly being communicated. Given that function words are so difficult to control, examining the use of these words in natural language samples has provided a nonreactive way to explore social and personality processes. Much like other implicit measures used in experimental laboratory studies in psychology, the authors or speakers examined often are not aware of the dependent variable under investigation (Fazio and Olson, 2003). In fact, most of the language samples from word count studies come from sources in which natural language is recorded for purposes other than linguistic analysis and therefore have the advantage of being more externally valid than the majority of studies involving implicit measures.

For this reason, function words are particularly useful in uncovering the relationship between intent and actual behaviors as they occur outside the laboratory. CLASSIFICATION SCHEME FOR THREATS One of the difficulties in examining threatening communications and actual behaviors is that researchers typically do not have access to a large group of similar documents on threats and subsequent behaviors. In addition, threats differ tremendously in form, type, and actual intent. Also, situational features across multiple threats cannot be cleanly or confidently classified into discrete categories in order to generalize to new threats. Many of these difficulties in research on threatening communications overlap with the difficulties in research on deception, for which empirical and naturalistic research has made considerable progress through the use of computerized text analyses (for a review, see Hancock et al., 2008). Comparison with Features of Research on Deception Deception has been defined as “a successful or [an] unsuccessful deliberate attempt, without forewarning, to create in another a belief the communicator considers untrue” (Vrij, 2000, p. 6; see also Vrij, 2008).

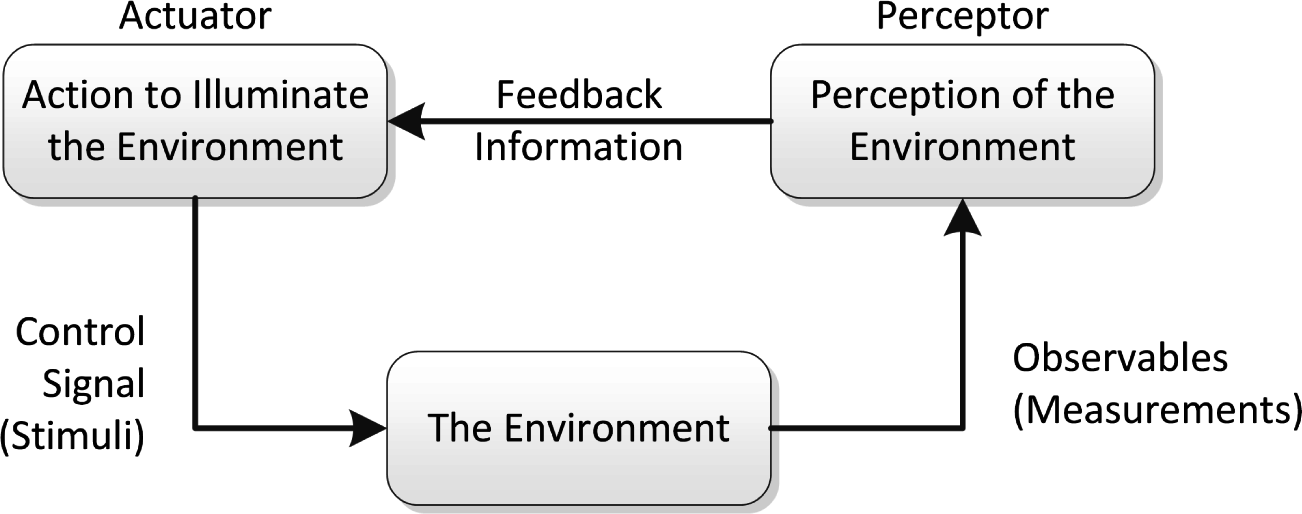

This commonly accepted definition of deception notes several features that could be used to succinctly define threatening communications within the task of predicting behaviors (see ). Specifically, Vrij’s definition includes information about outcome, intent, timing, social features and goals, and a psychological interpretation of the actor.

Threatening communications can be compared along all of these features. A threatening communication will likely carry the language cues used. In deception if the communicator knows that the message is false (i.e., has no intent to substantiate the threat). This situation is akin to “bluffing,” when a threat is made to achieve some goal(s) by creating in another a belief that the threat is real, when the communicator is aware that it is not.

This suggests that, for text analysis of threatening communications, language cues that have reliably been found to signal deception can be used to classify this type of threat as being less likely to be fulfilled. When the communicator knows that the threat is true (i.e., has real intent to substantiate the threat), language cues that have reliably been found to signal honesty can be used to classify this type of threat as being more likely to be fulfilled. The distinction between deception and threatening communications regarding timing is also an important point. Most language samples of deception come from retrospective accounts of some event. With language samples of threatening communications, often the threatening message is revisited after the act.

However, a threat, by definition, is received before the act of harm, and so the language samples analyzed to investigate threats versus deceptive messages typically come from different time points. With some threats there is the possibility of intervention. These features permit classification of four different types of threats (see ). Threats that might have the language features of deception are bluffs and latent threats. Threats that might have the language features. TABLE 1-2 Classification Scheme and Features of Threats Feature Type of Threat Real Threat Bluff Latent Threat Nonthreat Outcome Fulfilled Unfulfilled Fulfilled N.A. Intent Deliberate Deliberate Deliberate Not deliberate Timing Forewarning Forewarning No forewarning N.A.

Social features/goals Communicate harm Communicate harm Communicate no harm Communicate no harm Psychology of actor Communicator considers true Communicator considers untrue Communicator considers untrue Communicator considers true Language features of deception Honest Deceptive Deceptive Honest NOTE: N.A. = not available. Of honesty are real threats and nonthreats. Briefly described, a real threat is made known to the target before the harm occurs, with real intent to carry through on the threat. An example would be President George H. Bush’s threat to Saddam Hussein to leave Kuwait or a coalition attack would follow. In this case, the threat was directly communicated beforehand and was followed by the promised action.

A bluff is a threat that is made known to the target but with no intent to act on the threat. Multiple examples can be found in the speeches of Saddam Hussein, who explicitly stated and implicitly suggested that his army had the capability of inflicting mass casualties on coalition forces prior to both the Persian Gulf War of 1991 and the more recent war beginning in 2003. Latent threats are those that are concealed to the target before the harm occurs, with real intent to carry through on the threat. An example might be the case of Bernard Madoff, who was recently imprisoned for masterminding a Ponzi scheme that bankrupted hundreds of innocent investors. Many people invested their money with Madoff under his guise of a trusted financier. In this case, no threat was communicated, but his communications with victims likely would have shown linguistic markers of deception. Nonthreats are communications from people who have no intent to harm.

Indeed, nonthreats can be considered control communications in the sense that the speaker speaks honestly about events, actions, or intentions that the speaker believes to be nonthreatening. Nonthreats, like all other forms of threat communication, carry with them another potentially vexing dimension: the role of the listener or target of the communication. Is based on the speaker’s intent and behaviors, not the listener’s. It is possible that a speaker can issue a true threat but that the listener perceives it as a bluff. By the same token, latent threats and nonthreats can variously be interpreted in both benign and threatening ways. Failure to adequately detect a real threat or to falsely perceive a true nonthreat may say as much about the perceiver as the message itself.

For example, Saddam Hussein’s apparent failure to appreciate coalition threats in both 1991 and 2003 very likely reflected something about his own ways of seeing the world. Just as there are likely personality dimensions of people who deny or fail to appreciate real threats, a long tradition in psychology has been interested in the opposite pattern—the belief that a real threat exists when actually one does not. Dozens of examples of this can be seen in American politics, especially among those on the extreme left and right. During the George W. Bush years, many far-left pundits were convinced that the administration was planning to do away with the First Amendment.

Currently, many right-wing voices claim that the Obama administra. Tion wants to outlaw all guns—resulting in record sales of firearms and ammunition. From a linguistic perspective it is important that researchers explore the natural language use of both communicators and perceivers. For example, Hancock et al. (2008) have shown linguistics changes on the part of a listener who is being deceived, demonstrating that deception might be better detected and understood by considering the greater social dynamics in which it takes place (see also Burgoon and Buller, 2008, for a review of Interpersonal Deception Theory).

Situations are dynamic, and there are possibilities that real threats could be revoked or unsuccessfully attempted or that bluffs might be carried out under pressure. However, the key feature in language analyses is that an attempt is made to understand the psychology or deep-structure processes underlying the threats. In this regard, the personality or psychological states of both speakers and targets can be assessed in order to better understand the nature, probability, and evolving dynamics of a given threat. REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ON COMMUNICATED INTENT AND ACTUAL BEHAVIORS USING TEXT ANALYSIS To distinguish between real threats and bluffs, or between latent threats and nonthreats, the first step is to assess whether or not a given communication is deceptive.

To detect deception, computerized text analysis methods have been applied to natural language samples in both experimental laboratory tests and a limited number of real-world settings. Typical lab studies induce people to either tell the truth or lie. Across several experiments with college students, researchers have accurately classified deceptive communications at a rate of approximately 67 percent (Hancock et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2004). Similar rates have been found for classifying truthful and deceptive statements in similar experimental tests among prison inmates (Bond and Lee, 2005). The most consistent language dimensions in identifying truth telling have included use of first-person singular pronouns, exclusive words (e.g., but, without, except), higher use of positive emotion words, and lower rates of negative emotion words. Note that the patterns of effects vary somewhat depending on the experimental paradigm.

Correlational real-world studies have found similar patterns. In an unpublished analysis by the second author and Denise Huddle of the courtroom testimony of over 40 people convicted of felonies, those who were later exonerated (approximately half of the sample) showed similar patterns of language markers of truth telling, such as much higher rates of first-person singular pronoun use. A more controversial but interesting real-world example of classifying false and true statements is in the inves. Tigation of claims made by Bush administration officials in citing the reasons for the Iraq war. Specifically, Hancock and colleagues (unpublished) examined false statements (e.g., claims that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction or direct links to al-Qaeda) and nonfalse statements (e.g., that Hussein had gassed Iraqis) for words previously found to be associated with deceptive statements. It was found that the statements that had been classified as false contained significantly fewer first-person singular (e.g., I, me, my) words and exclusive words (e.g., but, except, without) but more negative emotion words (e.g., angry, hate, terror) and action verbs (e.g., lift, push, run). Across the various deception studies, the relative rates of word use signaled the underlying psychology of deception.

Deception involves less ownership of a story (i.e., fewer first-person singular pronouns) and less complexity (i.e., fewer exclusive words), along with more emotional leakage (i.e., more negative emotion words) and more focus on actions as opposed to intent (i.e., more action verbs). Based on the use of these words, approximately 77 percent of the statements made by the Bush administration were correctly classified as either false or not false.

Note that these numbers are likely inflated since estimates of the veracity of statements is dependent on the selection of statements themselves—as opposed to a broader analysis of all statements made by the Bush administration. It is important to note that the strength of the language model is that it has been applied to a wide variety of natural language samples from low- to high-stakes situations.

The degree to which language markers of deception were more pronounced in high-stakes situations relative to low-stakes situations is encouraging. Being able to classify the veracity of high-stakes communications with greater confidence could lead to more efficient allocation of resources for interventions.

Real Threats A real threat is one that is believed to be true by a speaker or writer, and so linguistic markers of honesty would likely appear in a threatening communication. The next step, then, would be to assess the likelihood of actual behavior. One area in which text analyses have informed psychologists of future behavior is in the written literature and letters of suicidal and nonsuicidal individuals.

In one study, Stirman and Pennebaker (2001) analyzed the published works of poets who committed suicide and poets who had not attempted suicide. Poets who committed suicide had used first-person singular pronouns at higher rates in their published poetry than those who did not commit suicide. Poets who committed suicide also used fewer first-person plural pronouns later in their career than did poets who did not commit suicide. Overall, the language used by suicidal.

Poets showed that they were focused more on themselves and were less socially integrated in later life than were nonsuicidal poets. Surprisingly, there were no significant differences in the use of positive and negative emotion words between the two groups and only a marginal effect of greater death-related words used by the poets who committed suicide. Similar effects have been found in later case studies of suicide blogs, letters, and notes (Hui et al., 2009; Stone and Pennebaker, 2004). These results highlight the importance of linguistic style markers (assessed by word count tools) as potentially more psychologically revealing than content words (which would more likely be the focus of judge-based thematic coding). Stated intentions are not necessarily threats. One area in which follow-through of stated intentions has been studied is in clinical psychology. In psychotherapy, patients typically state an intention to change maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

Mergenthaler (1996) used word counts to identify word categories that characterize key moments in therapy sessions in order to provide an adequate theory of change. He found that key moments of progress are characterized by the co-occurrence of emotion terms and abstractions (i.e., abstract nouns that characterize the intention to reason further about that term) in a case study and in a sample of improved versus nonimproved patients. These suggest that being able to express emotions in a distanced and abstract way is important for therapeutic improvements. The text analysis programs used by these clinicians, such as Bucci’s Discourse Attribute Analysis Program (Bucci and Maskit, 2005), are similar to LIWC in that they use a word count approach and many of their dictionary categories are both grammatical and empirically derived. However, the grammatical categories for the clinical dictionaries are broad (i.e., they throw all function words into a single category), and their empirically derived categories are based on psychoanalytic theories and clinical observations. The advantage of all word count tools for the analysis of therapeutic text is that word counts tend to be a less biased measure of therapeutic improvements than clinician’s self-reports (Bucci and Maskit, 2007).

In addition, word count tools can be assessed at the turn level, by conversations over time, and for the overall total of all interactions, making word count approaches a powerful tool for assessing follow-through of stated intentions. Another area in which follow-through of stated intentions has been examined is in weight loss blogs (Chung and Pennebaker, unpublished).

Diet blogs were processed using LIWC and assessed for blogging rates and social support. One finding was that cognitive mechanism words (e.g., understand, realize, should, maybe) were predictive of quitting the diet blog early and of gaining weight instead of losing weight.

This finding. Was consistent with previous literature which found that attempts at changing self-control behaviors typically fail if an individual is stuck at the precontemplation or contemplation phase of self-change (Prochaska et al., 1992, 1995). Instead, writing in a personal narrative style and actively seeking out social support were predictors of weight loss. Use of cognitive mechanism words, then, can signal flexibility in thinking, and perhaps less resolve, or coming to terms with failure.

Since the blogs tracked everyday thoughts and behaviors in a naturalistic environment (i.e., not in a laboratory or clinical study) and were not retrospective reports of the entire self-change process after success or failure, the findings were likely more reflective of the various stages of self-change, instead of a description of a memory of the change. Accounts of a narrative recorded during the time in which an event happened or prospectively instead of simply retrospectively are important in generalizing findings from language studies to threat detection. Studying the nature of threatening communications can come from the study of terrorist organizations and their communications, as interviews with world terrorists are rare (Post et al., 2009). Note that not all communications by terrorist organizations are threats. However, comparing the natural language of violent and nonviolent groups can tell us about the psychology of groups that will act on their threats (Post et al., 2002).

In one study, both computerized word pattern and word count analyses of public statements made by Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, from the years 1988 through 2006, were examined (Pennebaker and Chung, 2008). Initially, the 58 translated al-Qaeda texts were compared with those of other terrorist groups from a corpus created by Smith (2004). The alQaeda texts contained far more hostility as evidenced by their greater use of anger words and third-person plural pronouns. As for the individual leaders’ use of language over time, bin Laden evidenced an increase in his use of positive emotion words as well as negative emotion words, especially anger words.

He also showed higher rates of exclusive words (e.g., but, except, exclude, without) over the past decade, which often marks cognitive complexity in thinking. On the other hand, al-Zawahiri’s statements tended to be slightly more positive, significantly less negative, and less cognitively complex than those of bin Laden. He evidenced a surprising shift in his use of first-person singular pronouns from 2004 to 2006. This was interpreted as indicating greater insecurity, feelings of threat, and perhaps a shift in his relationship with bin Laden.

The word count strategy, then, allowed for a close examination of the psychology of the leaders in a way that otherwise would not have been possible. While much of the above review has been focused on word count approaches, it is worth noting the judge-based thematic analysis approach. Of Smith et al.

(2008) in studying the language of violent and nonviolent groups. Specifically, instead of having a computer count a set of target words, these researchers had trained coders manually interpret and rate the communications of two terrorist groups (central al-Qaeda and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula) and two comparison groups that did not engage in terrorist violence (Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Movement for Islamic Reform in Arabia). Among some of the complex coding constructs examined were dominance values, which included any statements where subjects were judged to have or want power over others (see Smith, 2003; White, 1951), and affiliation motives, which included statements where subjects were judged to have a concern with establishing, maintaining, or restoring friendly relations with others (see Winter, 1994). The results from their analyses and the results from previous studies on terrorist and matched control groups (Smith, 2004, 2008) showed some consistent findings.

Specifically, the violent groups’ communications contained more references to morality, religion/culture, and aggression/ dominance. The violent terrorist groups expressed less integrative complexity, more power motive imagery, and more in-group affiliation motive imagery than did the nonviolent groups. These effects were present in the language of violent terrorist groups even before they had engaged in terrorist acts, suggesting that these dimensions could potentially predict the likelihood of violence by a group (Smith, 2004). Further research is needed in order to assess whether these judge-based dimensions will be found at higher rates within a single real threat versus nonthreats from within an organization.

In addition, this research would be more suitable for realtime or close to real-time analyses if the judge-based dimensions that are coded at high intercoder reliability rates could reliably be detected using computerized word pattern or word count indices. Bluffs Unlike a real threat, a bluff might contain markers of deception since it is one that is believed by the writer or speaker to be false. Although there are many instances of psychologists using deception in laboratory studies to experimentally manipulate states of anxiety, parents threatening to take naughty children to the police, and people threatening to leave their lovers, relatively few studies have examined the word patterns of bluffs. Although an arguable form of bluffing, several studies have examined the psychology of people who attempt suicide versus those who complete suicide.

Some researchers have argued that those who attempt but do not complete suicide have a different motivation—one that is focused on attracting the attention of others (e.g., Farberow and Shneidman, 1961). If failed attempts at suicide are considered a form of bluffing, it might be thought that the suicide notes of attempters would be different from those of completers.

A recent LIWC analysis of notes from 20 attempters and 20 completers found that there were, indeed, significant differences in word use between the two groups. Specifically, completers made more references to positive emotions and social connections and fewer references to death and religion than did attempters. The attempters (or, perhaps, bluffers) appeared to focus more on the suicidal act itself rather than the long-term implications for themselves and others (Handelman and Lester, 2007). Latent Threats A latent threat refers to the explicit planning of an aggressive action while at the same time concealing the planned action from the target.

In Godfather terms this could be an example of keeping one’s friends close but one’s enemies closer. History, of course, is littered with examples of latent threats—from overtures by Hitler to England and Russia, the Spanish with the Aztecs, and probably most world leaders who have made a decision to go to war. Hogenraad (2003, 2005) and his colleagues (Hogenraad and Garagozav, 2008), for example, used a computer-based motive dictionary (motives that are typically assessed through judge-based thematic coding) to assess the language of leaders during periods of rising conflict. Interestingly, the same pattern of results was found across multiple realworld situations (e.g., in a commented chronology of events leading up to World War II, in Robert F. Kennedy’s memoirs of events before the Cuban missile crisis, and in President Saakashvili’s speeches during Georgia’s recent conflicts with the Russian Federation) and in published fiction (e.g., William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and Tolstoy’s War and Peace). It was found that the discrepancy between power and affiliation motives becomes greater as leaders approach wars. Specifically, power motives are identified by words such as ambition, conservatism, invade, legitimate, and recommend—and increase in times before war.

Affiliation motives are identified by such words as courteous, dad, indifference, mate, and thoughtful and decrease in relation to power motive words before times of war. These results are generally consistent with the findings of Smith et al. (2008) for violent terrorist and nonviolent groups. An example of a latent threat is that of President George W.

Bush’s use of first-person singular pronouns during his (over 600) formal and informal press meetings over the course of his presidency (see ). Note that only press interactions in which he was speaking “off the cuff” rather than reading prepared remarks were analyzed. As can be seen in, there was a large drop in use of the word I immediately after. FIGURE 1-1 President George W. Bush’s use of first-person singular pronouns during his time in office. 9/11 and again with Hurricane Katrina.

Saul Feminism Issues And Arguments Pdf Viewer. Most striking were the drops that began in August 2002, just prior to Senate authorization of the use of force in Iraq. Perhaps this was when President Bush formally decided to go to war in Iraq, an event that caused attention to shift away from himself and on to a task instead.

Similarly, the decision to go to war demands a certain degree of secrecy and deception. A leader who does not want to alert the enemy of his intentions must, by definition, talk in a more measured way so as not to reveal hostile intent. Similar observations have been made by other researchers concerning the language that leaders use in planning for wars. If true, one can begin to appreciate how word counts can betray intentions and future actions. Analysis of the natural language of these political leaders highlights the ability of computerized word counts to reveal how people are attending and responding to their personal upheavals, relationship changes, and world events.

A within-subject text analysis of public speeches over time bypassed the difficulties in traditional self-reports (i.e., personally seeking out these leaders in their top-secret hideouts to ask them to fill out questionnaires with minimal response biases). Nonthreats and the Nature of Genres As noted earlier, text analysis of nonthreats is conceptually similar to study of a control group. In other words, most studies on threats have relied on a nonthreat control group. Such a group assumes a reasonable degree of honesty in the communication stream. Ironically, any discussion of a nonthreat group raises a series of additional questions about the defining feature of honest communications.

People use language differently depending on the context of their speech. A person talking with a close friend uses language differently than when making an address to a nation. Communicating to a hostile audience typically involves a different set of words and sentence constructions than when speaking to admirers.

Any computer analysis of threatening communication must take into account the context. For example, there is reason to believe that, for some people, honest formal speech can look remarkably similar to dishonest more informal language. A comparison of word use as a function of genres was first reported in a pioneering study by Biber (1988).

Using a factor analytic approach to word use, he found that different forms of writing (e.g., news stories, romance novels, telephone conversations) each had their own unique linguistic fingerprint. The present authors have amassed hundreds of thousands of texts spanning dozens of genres and found striking differences that reflect genre, the demographics of the speaker (e.g., age, sex, social class), the relationship between speaker and listener, and so forth (see Pennebaker et al., 2003; Chung and Pennebaker, 2007). FUTURE DIRECTIONS The use of text analysis to understand the psychology of threatening communications is just beginning. A small but growing number of experts in social/cognitive/personality psychology, communications, linguistics, computational linguistics, and computer science have only recently begun to realize the importance of linking relatively low level language use to much broader culture-relevant phenomena. Indeed, there is a sense that we are on the threshold of a paradigm shift in the social sciences. As can be gleaned from this review, very little research, to date, has focused specifically on computerized text analysis of threats. Several challenges and suggestions for future research are outlined below.

Cross-Discipline Cooperation Cross-disciplinary and cross-institution research can lead to an exponential growth in understanding and predicting threatening behaviors. The ability to address socially relevant questions using large data banks will require the close cooperation of psychologists, computer scientists, and computational linguists in academia and in private companies. The ability to find, retrieve, store, and analyze large and quickly changing datasets requires expertise across multiple domains. Creation of Shared-Text Databases A pressing practical issue that must be addressed is access to data. First, by increasing access to data from naturally occurring threats from forensic investigations and across laboratories, researchers can start to build a more complete picture of threatening communications and compare text analytic methods in terms of their efficacy for assessing threat features. A consortium or text bank would have to include transcribed threats of all genres, across various modalities, of varying stakes, and in multiple languages, along with annotations for common features with other corpora in the text bank.

In addition, the text bank would need to include language samples from nonthreats, such as transcripts for spoken language in everyday life (e.g., Mehl et al., 2001). The text bank could potentially be updated with annotations from study results, such as classification rates, psychological characteristics, and new findings as they are produced. The collection and maintenance of a large threat-related data bank must include data from four very different types of sources. The first is an Internet base made up of hundreds of thousands of blogs and other frequently changing text samples. As potential threats appear in different parts of the world, a database that reflects the thoughts and feelings of a large group of people can be invaluable in learning the degree to which any socially shared upheaval is reflecting and/or leading a societal shift in attention or attitudes.

Comparable publicly available databases should also be built for newspapers, letters to the editor, and so forth. These databases should be updated in near real time. A second database should be a threat communications base. Some of the contents might be classified, but most should be open source. Such a database would include speeches, letters, historical communications, and position statements of leaders and formal and informal institutions. Database should include a corpus of individual-level threats—ransom notes, telephone transcripts, television interview transcripts—that can provide insight into how people threaten others.

Such a database should also provide transcripts and background information on the people or groups being threatened. A third database should include natural language samples. To date, very few real-world samples of people talking actually exist. The closest are transcribed telephone calls (as part of the Linguistic Data Consortium; see, e.g., Liberman, 2009), which are recorded in controlled laboratory settings.

One strategy that has promise concerns use of the Electronic Activated Recorder (EAR; see, e.g., Mehl et al., 2001)—a digital recorder that can record for 30 seconds every 12 to 13 minutes for several days. Mehl and others have now amassed daily recordings of hundreds of people, all of which have been transcribed. Using technologies such as the EAR, we can ultimately get natural instances of a broad range of human interactions, including those that involve threats. Finally, threat-related experimental laboratory studies must be run and archived.

A significant concern of the large-database approach to linking language with threatening communications is that it is ultimately correlational. That is, we can see how events can influence language changes. Similarly, we can determine how the language of one person may ultimately predict behaviors. The problem is that this approach is generally unable to determine if language is a causal variable. A president, for example, might use the pronoun I less often before going to war. However, the drop in I is not the reason or causal agent for the war. Curious social scientists will want to know what the drops signify.

Such questions are most efficiently answered with laboratory experiments. An experimental laboratory study database could include both language samples from studies and any other data collected from the studies for further annotations. Beyond the Words: Personality, Social Relationships, and Mental Health On the surface, it might seem that the study of threatening communications should focus most heavily on the communications themselves. Indeed, it is important to know about the components of written or spoken threats.

However, threats are made by individuals to other individuals within particular social contexts. It is critical that any language analyses of threatening communications explore the individual differences of the threateners and the threatened within the social context of the interactions. To better assess the relationships between personality and language. Individuals of all ages, socioeconomic status, and cultures must be sampled, along with any language samples that can be acquired from political leaders (e.g., Hart, 1984; Post, 2005; Suedfeld, 1994; Slatcher et al., 2007).

Researchers should be encouraged to track threats that occur in everyday life. It is known from over 20 years of research studies conducted worldwide that, when asked to write about their deepest thoughts and feelings about a traumatic event, participants are often very willing to disclose vivid and personal details about highly stigmatizing traumas, such as disfigurement, the death of a loved one, incest, and rape (for a review, see Pennebaker and Chung, 2007).

The ability to collect naturalistic evidence of long-term secrets and deception, then, is promising. Studies might come, for example, from e-mail records from individuals in the community who had kept a secret from a spouse, a lover, friends, or their boss that implied various levels of harm.

Academics might also explore threats across various modalities in order to tap how a particular community or population experiences widespread threats, for example, from blogs, newspaper articles, or telephone calls (see Cohn et al., 2001, and Pennebaker and Chung, 2005). There has been much research showing that the odds of violent or approach behavior increase when mental illness is present (Dietz et al., 1991; Douglas et al., 2009; Fazel et al., 2009; James et al., 2007, 2008, 2009; Mullen et al., 2008; Warren et al., 2007). Tamil Fusion Songs For Dance Free Download. Once empirical research has reliably identified the linguistic features of mental illness, future research can investigate the degree to which threats are communicated by individuals with various mental illnesses and disorders. Culture and Language Threats can come from individuals and groups of varying languages and cultures.

The ability to assess a threatening communication in the same language it was produced is important because there are no perfect translations. Such communications must also be assessed within the context of cultural experts. Below, a text analytic approach is described that the present authors are developing to assess the psychology of speakers from other cultures and determine which features are lost or gained in translations. The use of LIWC in psychological studies has extended beyond the United States, where it was originally developed.

This has been made possible because the software includes a feature for the user to select an external dictionary to reference when analyzing text files. This feature, along with the ability of LIWC2007 to process Unicode text, has enabled processing of texts in many other languages. Currently, there are validated dictionaries available in Spanish (Ramirez-Esparza et al., 2007), German.